He is survived by his 1 daughter, Catherine Rand, from his first marriage to Ann Rand. She was born in 19xx and currently lives in Cleveland, OH with her 2 sons XXX and XXX.

On November 28th at his funeral, Catherine gave a touching tribute to her father, who she had immense love for. Reprinted with her permission, here is what she said of her father:

My father’s death has been one of the saddest moments of my life. I am deeply grateful to have spent the final four days of his life by his side, stroking his forehead and holding his hand. This was a time of healing for me.

As my father lay in a coma, well beyond hope of a medical miracle, I prayed for God to take him soon. Fiercely determined and unrelenting in life, it was difficult for him to let go of life. His labored breathing and non-responsiveness were agony to watch. And then, a miraculous thing occurred. As I walked down the long hallway filled with dying and tears, I noticed a spectacular scene out of another patient’s window: a magnificent sunset. The extraordinary nature of this particular sunset beckoned me away from my father’s bedside, across the hall and up a small stairwell in which there was a picture window facing West. I watched, spellbound, the incredible unfolding of this tapestry of colors: dazzling pink, soft lilac blue, streaked orange, deep blue. A symphony of hues and dimensions abounded. Most spectacular was the center view in which the setting sun painted a throne of clouds a brilliant, shimmering gold. Gentle blue seahorse-shaped clouds drifted delicately in front, like little souls welcoming others. It truly resembled the Gates of Heaven. I yearned for my father’s soul to enter these golden heavens and be at peace. I believe this was indeed a sign of deep respect from above. This was God’s magnificent painting to commemorate the passing of this great artist. I watched the beautiful scene until the colors had faded and night approached. Two hours later, my father passed into the night sky. My prayers were answered.

At the 2015 exhibit of Rand’s work in New York City at the Museum of the City of New York, Catherine gave a touching glimpse into what it was like being his daughter as well as other never-before-heard pieces of information about his family life.

Good evening, it is a great honor and a privilege to be here, tonight.

I have been given five minutes to speak about what it was like to be Paul Rand’s daughter. Some of you in the room knew my father. Those of you who did, know that is an impossible task! But I will do my best.

In two words, not easy! But it was always interesting. My father was the most brilliant, creative, fascinating and difficult person I have ever known.

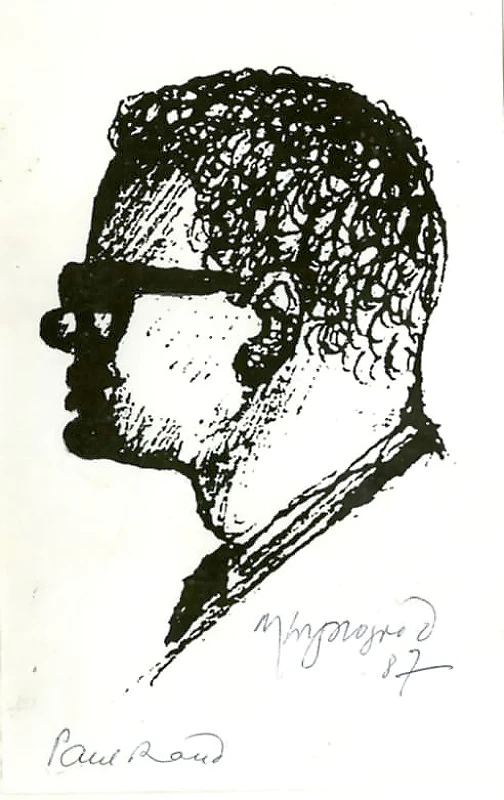

I am proud to be his daughter. I loved him dearly, and always wanted him to be proud of me. My father had a very difficult childhood. He grew up poor in an Orthodox Jewish family in Brooklyn. He had an identical twin brother, Philip, whom he both adored and envied. Philip was much more extroverted and socially at ease than he was. His parents owned a small grocery store and my father and his brother had to sleep in a loft where the bread was stored, and there were rats. My father absolutely hated rodents. My grandfather was a gentle, sweet, pious man, and my grandmother was the opposite. She ruled the roost with an iron fist. She had a pronounced hunchback, a crooked nose, and wiry white hair she wore in a bun—she looked exactly like the Wicked Witch of the West to me as a child and I was completely afraid of her. I never heard one positive word come out of her mouth. I was once told that the reason she didn’t say anything encouraging or positive to my father or me was because it was considered to be a jinx, in a certain branch of Judaism. My father drew like an adult at the age of three with charcoal he snuck from the fire, receiving not one iota of encouragement from his parents because drawing was essentially considered a sin, as it represented the “reproduction of the graven image.” I was awed that in spite of such blatant discouragement, he persisted. My father’s talent and drive were so intense that wild horses could not have stopped him. One terrible story I remember hearing from my mother happened when my father and his brother were about five or six years old. Their mother had gone to the store and they decided to mop the kitchen floor to make her happy. One of them accidentally knocked the bucket over and suds bubbled up everywhere. When my grandmother returned she was so angry that she whipped them severely. This is not the kind of childhood that engenders emotional well-being. My father was so driven to pursue his passion that he lied about his age to get into Pratt and Parsons art schools. At fourteen, he took the subway into the city at night, after a full day in high school. My father was ashamed that he only went to art school and not college, although he was awarded many honorary degrees throughout his career. He was one of the most well-read people I know, usually reading at least ten books at a time.

You might not be aware that my father was a very picky eater. While he did not keep Kosher, he did not like to eat butter or cream with his meals. My father would bark to the server that he did not want any cream or butter on anything—“Just plain!” Once he took my college boyfriend and me to a very elegant French restaurant in Boston. When he ordered, he loudly stated, “No cream! No butter! Just plain!” Within minutes the Chef came out with her hands on her hips and said, “Sir, do you realize that this is a FRENCH restaurant?? And in French cuisine nearly everything is made with cream and butter?!” Andrew and I wanted to creep under the table.

My father was the most visually oriented person I have ever met. In some ways, this was a curse because he was bombarded by visual stimuli everywhere he went. Perhaps this is why he always worked at home and had his clients and students come to see him. His home was his shrine. It was serene, stunningly beautiful, modern and so elegant in its simplicity and grace. He felt most at peace in his home or in Europe, where design and beauty are abundant. My mother told me that when my father was depressed she would encourage him to take her to Europe, as that elevated his mood.

It must have been very difficult to be Paul Rand, in part because of his overwhelming visual perception. He absolutely could not stand what he perceived as ugly. On one occasion when he came to visit us in Cincinnati and my son Troy was about two years old. We went to a Bob Evans restaurant, where he reeled at the sights: “Look at that wallpaper with that rug! Oh God! Those pictures! Look at that lady’s outfit!” While I would be mortified by his usually too loud comments, I can now see that he almost felt assaulted by visual stimuli. Most of us don’t suffer from what we see.

My parents divorced when I was three and a half, and I never lived with my father again. My mother and I moved to Manhattan, and I saw him every other weekend until I was nine when we moved to Los Angeles. The visits became much less frequent then. He might come to LA once or twice a year for a weekend, and I would go to Weston for a two or three weeks in the summers. My mother told me that my father adored me when I was little and still lived with him. When I was a colicky baby, my father played the accordion to soothe me to sleep. He loved to tell me that story. I believe I was indeed the apple of his eye then. Sadly for both of us, life tore us apart and it was never the same again. My father lived for his work. He was not a people person. He could be crass and cruel. I remember times when students came over to show him work they had toiled over and his loudly exclaiming, “This is shit!” As hard as he was on me, he was more brutal with them. Although my father wrote so beautifully about art, he was almost coarse when talking about it. And as playful as his art was, he was sour and serious much of the time. It almost seemed as if he only had fun when drawing or creating. Whenever he was at a restaurant, he drew all over the tablecloths—the most playful and beautiful things. I wish I had kept some of them!

I once asked my father what I could do that would please him, and he said, “Marry a Jewish man.” I didn’t. He announced he wouldn’t come to my wedding unless we were married by a Rabbi. This proved quite difficult since I had not really been raised Jewish and did not identify as Jewish, and my ex-husband, John, was an Atheist who had been raised Methodist! Happily, my father did come to my wedding, and did walk me down the aisle. I know if there is a Heaven, he must be very happy now because my boyfriend of the past five years, Howard Wolkoff, is Jewish. So I am finally partnered with a Jewish man!

My father was an artist, designer and genius. My mother was an architect, writer, painter and a great beauty. My genes were loaded with creativity, and I am quite a creative person. People wonder whether I inherited any of my father’s artistic talent. As a child, I drew prolifically. When I was eleven, I traveled to Spain with my mother and stepfather. One evening we had dinner at the Ritz Carlton of Madrid. It was always a late night out with adults for me, and I would draw to entertain myself. That night I drew bulls and all the waiters lined up to get one. I have always loved horses and used to draw horses, stallions in particular. One of my white stallions appeared in a book of children’s poetry when I was about eight, but sadly I don’t own a copy or even know the title. I stopped drawing when I was about thirteen. I was simply too intimidated by my father’s overwhelming talent to continue. My sons, Troy and Brody, are both profoundly talented in art. I believe that some of their grandfather’s gifts shine on in them. My other passions were music and writing, and although I wanted to become a professional singer for many years, I became a Clinical Psychologist. When you have a complicated childhood, sometimes you want to heal yourself by healing others.

The most healing moment I ever had with my father happened while he was dying. I am so grateful that I did not heed his mandate not to come see him. When I walked into my father’s hospital room four days before his death, he looked up at me smiling and said, “Hi Pooky!” I was blessed to spend my father’s final days at his bedside. He did not believe he was dying, although he had advanced colon cancer which had tragically been misdiagnosed as an ulcer, so it was not caught early enough for treatment to be effective. Since I was working as a geropsychologist in nursing homes at this time, I knew how to take care of older people. A death from colon cancer is very unpleasant. I sat next to my father nursing him as best I could, holding his hand all the while. I just wanted to be with him, to cherish that connection with him in his final hours. At one point he looked at me and said, “You are a terrific nurse!” The next day he said to me, “Catherine, you are completely transformed.” I replied, “Daddy, I have always been this way.” My father was sarcastic to the end: “Well, it takes a crisis to bring it out!” And I said softly, “No, Daddy, it took a crisis for you to see it.” I guess that is the saddest thing to me about our relationship…my father couldn’t really see that I am a good person or to really know me until his dying hours… It meant the world to me that he finally seemed to know and appreciate me, and I am grateful for the days I spent with him at his parting.