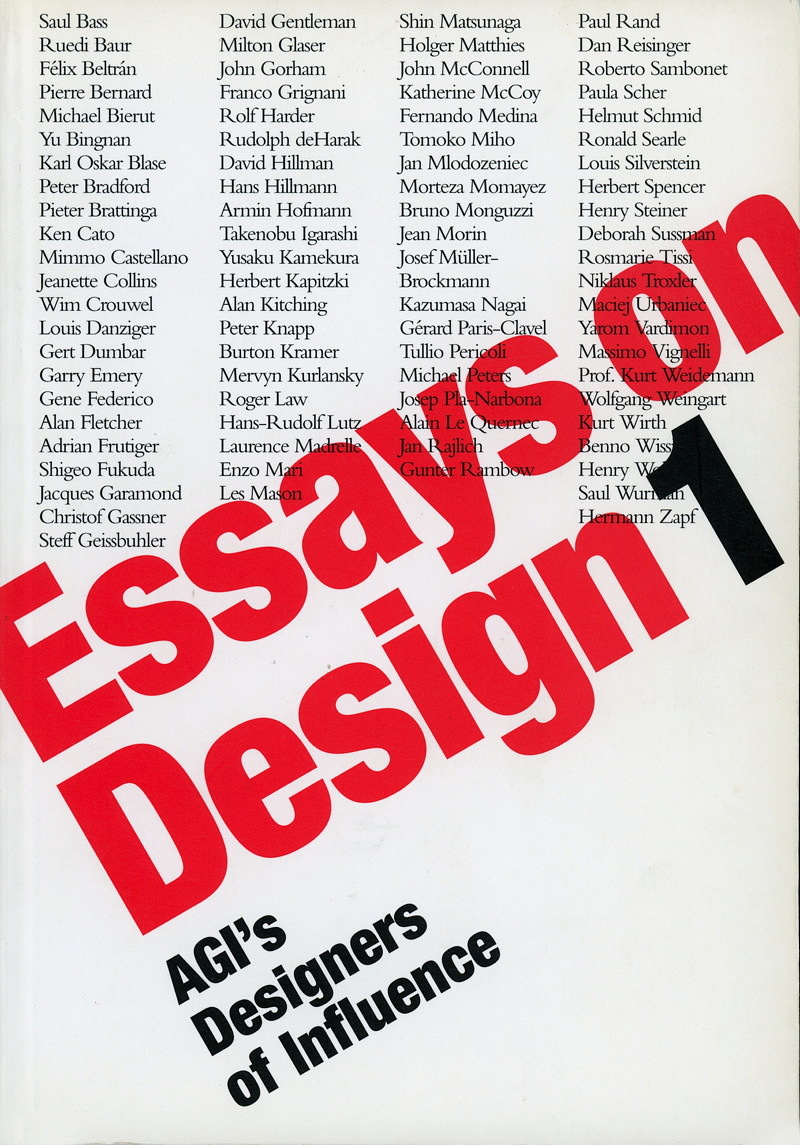

Set to become a standard work, this collection of the best writing from international designers brings together telling ideas of the most influential design thinkers of the century. From famous logos and product design to typography, these essays give a remarkable insight into the often anonymous world of design.

The Original Text

By Henry Steiner

A girl design student was reduced to tears, several other classmates were flabbergasted at being treated in a cold analytical manner, there were hurt sensibilities and anger, but I was enthralled: Paul Rand was giving his first critique of a graphic design class assignment in the Yale Art and Architecture School. It was the autumn of 1956.

Josef Albers, the former Bauhaus instructor, was running the Art School. Optical discoveries seemed to glimmer in every painter’s cubicle. Abstract geometric color studies were the norm, figurative art was virtually verboten.

In the basement of Louis Kahn’s elegantly spare concrete building, the class of ‘57 studied printmaking with Gabor Peterdi, photography with Herbert Matter, editorial layout with Bradbury Thompson. The graphic design department was headed by Alvin Eisenman whose tall, gangling presence was everywhere at once. He had started the department five years earlier and still heads it as I write this. He had a lanky body and a habit of staring at the ceiling, perhaps seeking inspiration. His nickname among the students was Ichabod Crane, after the character in Washington Irving’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow. He had the astonishing ability of identifying unfailingly the place of manufacture anywhere in the world of any blank scrap of paper a student presented to him.

After college in 1955 I had enrolled in the Graphic Design MFA program at Yale. At the end of my first year Alvin announced that Paul Rand would be joining the staff in the Fall term. I was overjoyed at the news.

Rand’s posters had brightened the dull section of Manhattan where I grew up. In my high school and college years I was aware of the Interfaith Day posters in the subway, the El Producto cigar boxes displayed in the candy stores, the advertisements for Ohrbach’s in The New York Times. In the Public Library on East 23rd Street I discovered Paul’s classic book Thoughts on Design with the splendid abacus photogram on the cover. I marvelled at the erudition of the text and was charmed by the witty visuals.

At Yale Paul always wore a jacket and tie to his weekly classes. The tie was invariably a black knitted one: once he wore it with a bright red shirt, an unusually bold sartorial statement for those decorous Eisenhower years. He was short and had a boxer’s head, massive, pugnacious, with close-cropped hair and a bristling energy about him. He wore glasses and his eyes twitched frequently; we nicknamed him Blinky. He was forty-two years old.

He spoke with a Brooklyn accent from his boyhood but with many scholarly allusions and frequent mots justes. His command of art history and philosophy were formidable and in any given session he might cite Corbusier, Henry James, Ozenfant, Tschichold, or AN Whitehead to make a point.

Once he digressed to demonstrate how enclosing a figure within a shape could energize it and drew upon Aristide Maillol’s signature as an example. This inspired me to create my own monogram. On another occasion he explained how the more sparingly one used a second color, “the more precious - in the good sense - it becomes”.

His method was to assign the redesign of an existing advertisement, poster or trademark. Along with our design, we had to write an explanation of the idea behind it on a 3” by 5” index card. The first assignment was to redesign an advertisement for cooking chocolate. The following week the index card requirement proved to be a stumbling block to many of my classmates who were unable to set down an idea. They talked of “shapes” and the girl who wept had described a “feeling” of Alice in Wonderland. She totally lost her composure when Rand said

If you don’t have an idea, you don’t have a design.

Along with the concept of requiring an idea at the start of the design process, Rand gave me another valued intellectual tool. This was contrast, which he said was the heart of any good design. It could be contrast of big and small, old and new, strange and familiar. He arrived at this theory based on his knowledge of Hegelian dialectics, Chinese Yin/Yang, Japanese Zen, and a smattering of Ecclesiastes.

As the school year continued we received other assignments: a corporate identity for US Lines, a poster for Italy, an announcement for a painter’s exhibition.

In his critiques, with one observation, Rand was able to make a design more effective. He did this in one case by blanking out an area with his hand, in another by turning a poster upside down. During one particular session, Rand relentlessly criticized and corrected the displayed posters in his intellectually honest and dispassionate manner. As he went through our creations, I kept waiting for his assessment of one which looked especially outstanding, but others seemed to occupy his attention. Finally a classmate, in a spirit of fairness, asked him why he had not commented on the poster which I admired. Paul seemed taken aback and replied: “I have nothing to say about it. It’s a fine design.” I believe his valid concern at that time was with improving weaker designs rather than complimenting achievement.

He once observed that any colors could be made to work together if they were separated by white or black bands, referring to Matisse and the windows of Chartres. The assistant lecturer for Paul’s course was Norman Ives, a disciple of Albers and his painstaking approach to the interaction of color. Norman sniffed: “Well, that’s taking the easy way out.” Rand shot back: “If you can do it the easy way, why do it the hard way?” A confrontation between Yankee idealism and Brooklyn pragmatism. (Rand respected Albers, however, and affectionately quoted his German accented definition of an intentionally designed optical trick as a “schvindle”.)

Most of my classmates were happier puttering with arrangements of the 19th-century wooden type fonts Alvin had collected for the school. They were initially unhappy with his cerebral, Apollonian approach to the assessment of their work, but I perceived that Rand was attempting to instil in us a rigor of analysis, a rational method of creation that he had achieved by studying the process in himself. Certainly, several of us were spurred on to producing the best work we could.

I made an effort to get to know Paul better. This resulted in an invitation to visit his home in Weston, a short train ride south from New Haven.

He was behind the house, clearing some fallen branches and pulling out weeds near the edge of his property. I helped him with this humble rustic activity. It was early autumn and still warm.

After a while we went into the kitchen where he drank a mixture of seltzer and orange juice; a fizzy combination which he recommended as being very thirst-quenching. He said he needed to be active and speculated that if he were in jail without the possibility of doing something constructive, of effecting change, he would probably kill himself.

Several years before, Rand had bought this lovely, undulating piece of land and built a charming house in the spare International Style with a flavor of Charles Eames and Japanese architecture.

It was a one-storey structure and consisted oflarge square white walls and clear glass panels which enclosed some spaces and allowed vistas from others. Inside it one had a sense of being pleasantly removed from the rest of the world. It was furnished with classic contemporary furniture, a zebra skin on a tile floor and several small paintings by modern masters. I recall a Picasso, a Klee, and there may have been a Mira - all artists who exerted an influence on Rand. The exception to this unarguable pantheon was a painting by Richard Lindner, a friend of Paul’s. There was also a painting by Paul of an overburdened burro, on which he later based an illustration for one of his children’s books. There was a studio wing to the building. A lithograph by Le Corbusier was on the wall. Paul worked here and had one assistant who came on weekdays. At the time he was drawing in his happy linear style an anthropomorphic cigar dressed as a big game hunter who had just bagged a lion.

Paul had been a wunderkind, becoming art editor of Esquire magazine in New York at the age of eighteen and setting a standard which would be maintained later by Henry Wolf. He then worked for Wm H Weintraub and Co. with Bill Bernbach who would subsequently start Doyle Dane Bernbach, an agency which set new standards for creativity in the 1950s and 1960s.

When I met Paul he had been working freelance for several years. His most recent coup was the IBM corporate identity. He was receiving a retainer of $10,000 a year as graphic consultant to the company which was then graduating from electric typewriters to computers.

At his home, Rand spoke with wonder about Saul Bass having called him long distance all the way from California to invite him to judge an exhibition on the West Coast. He was flattered because Bass was a design superstar at the time. In New Haven we would see his pioneering film titles for A Walk on the Wild Side, Anatomy of a Murder, The Man with the Golden Arm, etc.

I had been to New York with my class a few weeks before to view the 1956 AIGA show, which seemed to break new ground in graphic design. I was enthusiastic about the work of Herb Lubalin, but Rand found his stacked capitals a bit “zippy”.

At another time he was rather scathing about the typography of what he called the “Swiss yodelers”. Later, due to a friendship with Josef Muller-Brockmann he underwent a Pauline conversion (comparable to Stravinsky’s embracing of the tone row method of composition). Thereafter, his work and teaching included a lively interest in the grid system of layout. This was seen in his IBM annual reports of the early 1960s with their meticulous raster layouts and sensitive Garamond typography. The latter marked another change in Paul’s work, as before then he tended to rely heavily on either Futura or Bodoni.

Paul once described to me how, when he was working on the IBM identity, he kept going through type specimen books, until he hit on the German 1930s “City” typeface. He modified it to produce the famous logo; eventually he produced the present, striped version.

During one of his critiques he mentioned how important it was to move elements around on a page until one found the right positioning and how this could take hours or days. Behind the seemingly nonchalant spontaneity of Paul’s work lies much scholarship, thought and patient effort.

A friend once remarked on Paul’s apparent self-absorption, saying that at dinner the conversation with Rand went dead unless it centred on what Paul was doing or thought. There may be some truth to this observation, but then if one were privileged to have a conversation with, say, Gutenberg, would it not be silly to waste time discussing the price of cabbages in Mainz?

Once during that school year he brought to a class Raymond Savignac, the great Parisian aJfichiste, introducing him with relish for a language in which he was not at home, as “man cher wrifrere”. He also achieved a passable British accent in describing a visit to Henri Henrion’s London club a previous summer. Henrion claims that when he introduced Rand to Eisenman at the club, the subject of a visiting professorship was broached and Paul’s first question was “How much?”

I have mentioned the influence on Paul’s house of japanese architecture. He also treasured a plain cylindrical jardiniere covered in a regular pattern of neat blue Chinese calligraphy. Soon after arriving in Hong Kong I bought an identical piece of porcelain, one of the few objects I would never abandon if I were to leave Asia.

Rand’s interest in Asia was more theoretical than empirical: he made only one short visit to japan. I was told of his mischievous wit at a geisha party during that trip when one of the girls asked him where he came from. Realizing the difficulty the japanese have with certain consonants, he gave not his real place of origin but Brattleboro, a town in Vermont. The three syllables of this word form a perfect shibboleth for the japanese and all the geisha were tongue-tied attempting its pronunciation.

Paul had to relinquish the professorial position at Yale when he passed the age of seventy, but he continues to teach the “master classes” which Alvin created and at the Yale summer school in Brissago in Italian Switzerland.

I know that Paul never intended to cause distress to his classes but he felt it his duty to challenge and to improve. Many design students expect a teacher to disinterestedly “bless” their offerings. This indulgent attitude has led to the distressingly low standard of professional ability shown by the majority of design graduates today. As a teacher, Paul was simply thoroughly involved with and absorbed in his profession. Others dabble at their work, Paul lives as a consummate designer, creating his environment, meeting admired colleagues, reading widely but with relevance to his calling.

He remains wholly dedicated to his craft and continues to live totally as the archetypal graphic designer of our time. In Milton Glaser’s words, “He keeps us honest.”

I understand he has modified his technique so that rather than discuss the displayed homework with all the class present, he now has private tutorials with one designer at a time in his office. Kinder and more face-saving perhaps, but what a loss of opportunity to learn from each other’s successes and failures, to watch a master swiftly rearrange a composition to improve its message, to observe him doggedly challenge a design student on his line of reasoning and find an idea hidden in the piece.

Paul’s gruelling critiques proved invaluable for his students and during his thirty years Yale produced a remarkable number of outstanding designers. Once you had learned from Paul to analyse the problem, to articulate your solution and to be prepared to defend it in the face of his relentless probing, you were ready to face any client presentation with serene confidence.

On two recent stays in New York I was privileged to breakfast with Paul and his wife Marion (who had been manager of design for IBM) at the Yale Club during their overnight visits to Manhattan. Marion has slightly softened Paul’s pugnacity though his tight helmet of hair is white but still bristling. His work remains vigorous; his latest, most notable project is the identity for Steven Jobs’ company, Next. At the most recent breakfast our conversation turned to Paul’s religion. He is not only a born Jew, but a devout one. While I now hardly enter a synagogue, even for the high holy days, Marion remarked that Paul not only attends Schul but prays at home daily in the ancient, prescribed manner.

“Well,” he explained, “it keeps me humble.”

My reply was: “Paul, perhaps you need it more than I do.”